See additional footage of D’Angelo

See List of Dreamers

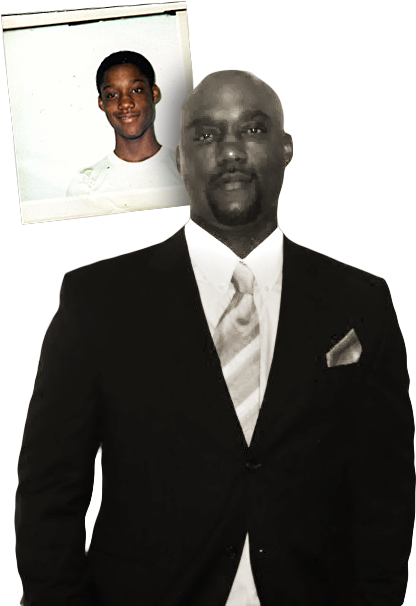

D’Angelo Dotson

My mom told me she worried from the day I was born about how I was going to be in life, how she wanted me to be better than her. I think every parent wants that; every parent should want that. When she found out about the I Have a Dream program she was relieved. It meant so much more to her, at the time, than it did to me. I was a little too young to fully understand the impact this would have on me. I pretty much thought, Oh, cool, we get to go on trips twice a year. Or something like that. But I’ve come to realize it was a lot more: It was somebody giving you a chance to be something, when it would have been very difficult on your own, if not impossible. At least, not at the rate that people did.

I think we Dreamers felt like we were kind of set apart from everybody else; there were people that actually cared about our education and our wellbeing, and tried their best and gave extra time to help us focus and be more successful. Day in, day out, they’re on the phone with you. They come see you on weekends. Going that extra mile. I'm thankful for that. Without that, probably a good portion of us might not have been as successful as we are now.

To be honest, I mean, I would have probably became a statistic. Or at least not reached the level of success that I've had over these past several years. In my neighborhood, it was an average of two out of five people selling drugs or dropping out of school. One out of 10 people being either a victim or committing homicide. My mom, you know, definitely, she kept me out of trouble, tried to her best. But she couldn't be with me 24/7, so if it wasn't for having this influence at school, you know, where you end up spending almost a third of your life up until you're 18, anyway, who knows what would have happened. It's good to have as many people as you can in your life that want you to see more than what's in your environment, to see the better, more positive, aspects of life. You know, don't become your environment, be better than it. If it weren't for the program, I know I wouldn't have been able to have the chance—or the courage—to really leave my comfort zone, to leave home. And although, there's nothing wrong with being at home, we all should aspire to higher things in life. Even if you fail.

I know I wasn't always the easiest student, the best student. I had potential, but I had a hard time focusing. But one of the big things I always remember, was that despite the fact that I was a little difficult, no one gave up on me. They put even more effort into ensuring that I nailed down the subjects and got my assignments in and everything like that. I mean, Mrs. Rumbarger has come to my house and sat there, at times, and helped me through my assignments. It showed me that if I put forth the effort, then the rewards or the benefits were going to be great. And it showed me that a lot of people were investing their hopes and their emotions and their time and their faculties in my future. And that right there really made me feel like I could do a lot more than what I thought I was capable of.

I went to Mt. Vernon Academy, and being away from home and everything like that, it was a lot more independence and freedom. And, of course, when you're at that age, you have a lot more opportunity to mess up, because you get sidetracked by everything else other than your studies. So, I had some difficulty with that. I actually had trouble my junior year, and I had to leave the school. It was, I'm going to say, shenanigans of a teenage boy, pretty much. It was a silly school prank that went bad. When I left and I had to come back to D.C., I went to Eastern. That was probably one of the most difficult times in my life. I could see that Mrs. Rumbarger and Mr. Bumbaugh were rightly disappointed, but they didn't make me feel any worse than I already was feeling. Because I felt disappointed, myself. I finally came to the realization that I had a very rare opportunity, and I was messing it up.

I at least tried to apologize for, you know, my behavior back then. I was a little bit of their special project at times. But after I got in trouble—that was really, really close—I made sure that I tried to find balance, you know, have fun, but get my work done first. I try to keep that philosophy—which now I tend to be way more work than I am fun. My daughter tells me I need to lighten up.

At Eastern, I actually had one of my best years. I almost had a 4.0 GPA. I had to reapply to get back into Mount Vernon for senior year. They convened the school’s faculty board. And on a probational basis, I came back, on the promise that I wouldn't get in any more trouble and would adhere to school policy and everything. After I got a second chance, of course, I didn't get in any more trouble, and I graduated.

I started at Pacific Union College, and I’ve got to say, I wasn’t as mature as I needed to be. I finished a year and then I thought, instead of wasting a lot of money—it was around $24,000 a year—and time, you know, mine and other people’s, I thought maybe I should take a break and try to figure out what exactly I wanted to do and what I wanted to get out of my education. I came to the decision to join the military, and signed up for college money and a two-year enlistment. Fifteen years later, I had traveled all over the world, I lived in Asia, spent some time in Africa, and served in almost every major conflict, from the Balkans, Bosnia and Macedonia, Kosovo, to four tours in Iraq, not counting my assignment now. That was an education in and of itself.

After I got out of the military, I landed here (in Iraq) as a military equipment instructor. My client is the Iraqi government. My contract is up in July, so this summer, I’m planning on re-enrolling in school. So I can meet that one thing I haven’t done for my life that I’ve wanted to finish: I’m actually about 32 credits shy of my bachelor’s. I’ve taken a couple classes a year—actually 1.3 classes a year over 14 years.

The biggest thing I’m thankful for is the I Have a Dream foundation looking at me and giving me a shot. Because the environment a lot of us grew up in, I mean, it's very negative. Some of the people that we lived with were negative. So, a lot of times, the school is going to be the only chance for you to get away from this negative environment. For some kids, that's all they have.

Of course, we're told from a young age that, you know, you got to go to school, get your education, so you can get a good job, so you can make money, so you can have things. Well, a lot of people out there that were, you know, conducting illegal activity—they already had those things. And at my age. So, it was very tempting to, you know, circumvent the process. And I think that the Dreamer program, for me, made me want more than just material objects. It made me want to aspire to want to do the best for myself and want to be someone that I could respect, you know?

Of course, your opinion matters most, but at the time you're a child, you're looking for outward approval. But I think that seeing Mr. Bumbaugh graduating from an Ivy League college, and I'm thinking to myself, maybe I could do that. It put that seed of inspiration inside of you thinking that, you know, you can be more than just a little black child growing up in allegedly the most dangerous city in the world. And the fact that I lived there, grew up, and survived it, is an accomplishment in and of itself. You know, not even counting all the other things I've done in my life. Just being able to say that I lived through that, and I didn't let my environment affect me or drag me down. That's—that's a very positive thing, and that's something that I think all of us should go back and tell these children that, you know: I did it, so you can, too. You have just as much potential.